The Big Here Quiz – Watershed Awareness Test

2/22/2022

About 50 years ago, a naturalist named Peter Warshall created a "test" to help build watershed awareness. "You live in the big here. Wherever you live, your tiny spot is deeply intertwined within a larger place, imbedded fractal-like into a whole system called a watershed, which is itself integrated with other watersheds into a tightly interdependent biome." The quiz includes thirty questions (starting with "Point north" and ending with a few bonus questions) aimed at helping you to "elevate your awareness (and literacy) of the greater place in which you live." Give it a try.

About 50 years ago, a naturalist named Peter Warshall created a "test" to help build watershed awareness. "You live in the big here. Wherever you live, your tiny spot is deeply intertwined within a larger place, imbedded fractal-like into a whole system called a watershed, which is itself integrated with other watersheds into a tightly interdependent biome." The quiz includes thirty questions (starting with "Point north" and ending with a few bonus questions) aimed at helping you to "elevate your awareness (and literacy) of the greater place in which you live." Give it a try.

Loons "did not say good-bye and left no forwarding address"

by Doug Tifft

12/03/21

As for our particular loons, I would say they departed in mid-October, though they did not say good-bye and left no forwarding address. I happened to see four loon strangers on our end of the lake last week. They clearly were just stopping for a bathroom break and to empty their ashtrays. It was interesting to watch them because they seemed jazzed up — all that caffeine and flying through the night with the radio blaring talk radio from some crazed AM station.

Our loons are not banded so I can't be certain where they go. Dale [Gephart] seems to think they winter not far from him along the New Hampshire shoreline. He's probably not far from right. I understand that our guys only have a brief flight before they plunk down somewhere from the Maine coast down as far as the Cape Cod area or the Rhode Island shore.

I see the loons are in the news lately: one article about concentrations of toxic chemicals that move their way up the food chain to the fish they eat and can cause problems with reproductive health. This was based on close analysis of infertile loon eggs, mainly from the Squam Lake area. Our loons actually laid two eggs this year, with only one of them hatching. At the suggestion of Eric Hanson, I retrieved the abandoned egg and kept it in my freezer for him to pick up later in the summer for analysis in a lab. Another more recent news article just appeared about loons in the three northern New England states. It seemed to bear out this finding about more dud eggs. There were more nesting pairs this year but fewer successful hatches. Worrisome.

For the coming year I am hoping we get an upgrade to our loon nesting raft. The Loon Conservation Project received a chunk of that settlement from the oil spoil that killed a bunch of loons a while back. Our poor raft is made of logs and is getting rather low in the water after five seasons.

12/03/21

As for our particular loons, I would say they departed in mid-October, though they did not say good-bye and left no forwarding address. I happened to see four loon strangers on our end of the lake last week. They clearly were just stopping for a bathroom break and to empty their ashtrays. It was interesting to watch them because they seemed jazzed up — all that caffeine and flying through the night with the radio blaring talk radio from some crazed AM station.

Our loons are not banded so I can't be certain where they go. Dale [Gephart] seems to think they winter not far from him along the New Hampshire shoreline. He's probably not far from right. I understand that our guys only have a brief flight before they plunk down somewhere from the Maine coast down as far as the Cape Cod area or the Rhode Island shore.

I see the loons are in the news lately: one article about concentrations of toxic chemicals that move their way up the food chain to the fish they eat and can cause problems with reproductive health. This was based on close analysis of infertile loon eggs, mainly from the Squam Lake area. Our loons actually laid two eggs this year, with only one of them hatching. At the suggestion of Eric Hanson, I retrieved the abandoned egg and kept it in my freezer for him to pick up later in the summer for analysis in a lab. Another more recent news article just appeared about loons in the three northern New England states. It seemed to bear out this finding about more dud eggs. There were more nesting pairs this year but fewer successful hatches. Worrisome.

For the coming year I am hoping we get an upgrade to our loon nesting raft. The Loon Conservation Project received a chunk of that settlement from the oil spoil that killed a bunch of loons a while back. Our poor raft is made of logs and is getting rather low in the water after five seasons.

|

VINS Releases Fledgling Bald Eagle on Lake Fairlee

Text and photos provided by Grae O'Toole & Emily Johnson of VINS (Vermont Institute of Natural Science) 9/2/21 We received the fledgling Bald Eagle at VINS on 6/9/2021 after it had fallen out of its nest located on Camp Lochearn. A game warden and camp staff were able to get the eagle contained and transported to us shortly after it had fallen. Upon arrival an intake exam was performed to check for injuries. Rehabilitation staff found the eagle suffered a left clavicle fracture due to the fall and had maggots in one ear. Due to the heat and their lifestyle it is common to find nestling and fledgling raptors with fly eggs and maggots on or in the body sometimes. The eagle was treated for the maggots and the wing was wrapped for roughly two weeks. Once the fracture was stabilized the eagle was progressively moved to larger stalls until staff were confident the wing was ready to be exercised. The eagle spent 20 days in a large flight cage and was exercised three times a day to be sure to build up muscle strength before release. After 76 days in care the eagle was released near its nest location on 8/24/2021 at Lake Fairlee. The eagle flew out of its carrier and banked over the lake before landing in a nearby pine tree. Shortly after the eagle landed an adult eagle was seen flying over the lake with a fish in its talons heading towards the nest. Shortly after that the rehabilitated eagle's sibling was seen flying over the water following its parent to the nest, begging for fish the whole time. Rehabilitation staff are so excited this (not so little) fledgling eagle was able to be released back where it came from and are hopeful the parents and siblings will continue to teach the bird all it needs to know about living out in the wild. We are uncertain of gender. Given weight and size I would guess male, but I can't say for certain. Download a video of the release below.

| |||

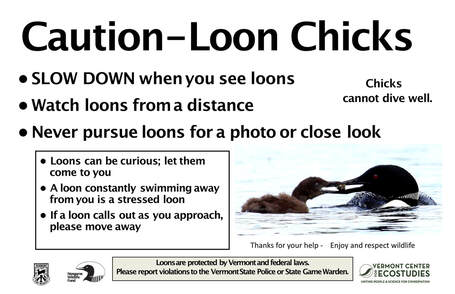

We have had some recent close encounters between boats and the loon family,

|

including one incident where a motorboat pursued the loons as they swam away. This is against the law. Loons are protected law by Vermont and federal laws. Please report violations to the Vermont State Police or State Game Warden, Jeffrey Whipple (cell phone 535-5220). Phoning in with the time of the incident, a description of what occurred, and the vessel number would be helpful.

You can also report a violation on The Vermont Fish and Wildlife website (your report can be anonymous if you prefer). You are also welcome to share observations with Doug Tifft, our local loon expert, via email. We have fewer than 100 surviving chicks a year in all of Vermont, so each of them counts. |

Lake Fairlee is a Natural Resource

by Dale Gephart

7/28/21

Lake Fairlee is a great natural resource. It teaches us about the environment. It provides an opportunity to find nature in small places and quiet moments.

This freshwater pond and its surrounding watershed display remarkable diversity. The varied habitats for plants and animals provide unique nurture in themselves. In addition, the juxtaposition between field and forests, land and water, wetland and stream creates seasonal and varied life cycles that take advantage of more than one habitat. Many animals and plants survive the winter via the protection of the lake. The forest retreats provide safe hibernation for animals of all classes.

The Department of Environmental Conservation is a remarkable Vermont resource. Naturalists from several departments provide support on Lake Fairlee to protect and to educate. We recommend this website which tells the story of our typical yet unique pond.

THE WEB OF LIFE

We are creating an inventory of all the life of our local "community." Using the base structure of the "Vermont Atlas of Life" on iNaturalist, we have set the Lake Fairlee watershed as the boundary for our documentation. We are providing "the observations" from ridgeline to ridgeline down the streams and into the lake on this map. We decided to focus on the watershed to demonstrate the interconnection and interdependence of all living things. While this “web of life” is invisible when looking out over the lake, it is not simply a concept or philosophy; it is the fabric of "how life works." When we look in the right places or with the right vision we see it. Models with arrows or graphs are not always the best way to demonstrate the connections. Perhaps a story is a good way to get the message across. Here is one recently posted to a local newsletter.

A SPRING STORY to illustrate the "web of life," by Dale Gephart

On the first spring walk in the woods, I made my first iNaturalist plant "observation." Yellow Trout Lily was dutifully photographed with my cell phone and then, back in cell tower range, I sent it to iNaturalist. After returning home, I logged onto the main iNaturalist map of our watershed. There the plant was with a green tag, Erythronium Americanum. The exact location is on a creek at the northwest corner of Lake Fairlee for everyone to see. The gray-green leaves mottled with brown or gray are said to resemble the coloring of a brook trout. I had seen two beetles with red necks on the open flower. I sent a second photo to iNaturalist without identification of these unknown beetles. Soon another citizen scientist identified the Red-necked False Blister beetle: Ischnomera ruficollis. Many questions. What were they doing there? Remarkably, Declan McCabe has an article on these beetles in the April 2021 edition of Northern Woodlands. Most likely, they were eating the pollen, transferring the pollen to other plants, and probably mating. There is a fair amount of diversity in the trout lily genome and DNA transfer is frequent.

Of interest, Yellow Trout Lily is a myrmecochorous plant, meaning that ants help disperse the seeds and reduce seed predation. To make the seeds more appealing to ants they have an elaiosome which is a nutrient-rich structure that attracts ants. (Elaiosomes are best seen locally in Bloodroot capsules following the flowering.) Having just read Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake and finding mycorrhiza are essential to my favorite hepatica patch in the woods, I wondered what was under the yellow trout lily. This abstract from New Phytologist shows the complexity of our knowledge of mycorrhiza:

7/28/21

Lake Fairlee is a great natural resource. It teaches us about the environment. It provides an opportunity to find nature in small places and quiet moments.

This freshwater pond and its surrounding watershed display remarkable diversity. The varied habitats for plants and animals provide unique nurture in themselves. In addition, the juxtaposition between field and forests, land and water, wetland and stream creates seasonal and varied life cycles that take advantage of more than one habitat. Many animals and plants survive the winter via the protection of the lake. The forest retreats provide safe hibernation for animals of all classes.

The Department of Environmental Conservation is a remarkable Vermont resource. Naturalists from several departments provide support on Lake Fairlee to protect and to educate. We recommend this website which tells the story of our typical yet unique pond.

THE WEB OF LIFE

We are creating an inventory of all the life of our local "community." Using the base structure of the "Vermont Atlas of Life" on iNaturalist, we have set the Lake Fairlee watershed as the boundary for our documentation. We are providing "the observations" from ridgeline to ridgeline down the streams and into the lake on this map. We decided to focus on the watershed to demonstrate the interconnection and interdependence of all living things. While this “web of life” is invisible when looking out over the lake, it is not simply a concept or philosophy; it is the fabric of "how life works." When we look in the right places or with the right vision we see it. Models with arrows or graphs are not always the best way to demonstrate the connections. Perhaps a story is a good way to get the message across. Here is one recently posted to a local newsletter.

A SPRING STORY to illustrate the "web of life," by Dale Gephart

On the first spring walk in the woods, I made my first iNaturalist plant "observation." Yellow Trout Lily was dutifully photographed with my cell phone and then, back in cell tower range, I sent it to iNaturalist. After returning home, I logged onto the main iNaturalist map of our watershed. There the plant was with a green tag, Erythronium Americanum. The exact location is on a creek at the northwest corner of Lake Fairlee for everyone to see. The gray-green leaves mottled with brown or gray are said to resemble the coloring of a brook trout. I had seen two beetles with red necks on the open flower. I sent a second photo to iNaturalist without identification of these unknown beetles. Soon another citizen scientist identified the Red-necked False Blister beetle: Ischnomera ruficollis. Many questions. What were they doing there? Remarkably, Declan McCabe has an article on these beetles in the April 2021 edition of Northern Woodlands. Most likely, they were eating the pollen, transferring the pollen to other plants, and probably mating. There is a fair amount of diversity in the trout lily genome and DNA transfer is frequent.

Of interest, Yellow Trout Lily is a myrmecochorous plant, meaning that ants help disperse the seeds and reduce seed predation. To make the seeds more appealing to ants they have an elaiosome which is a nutrient-rich structure that attracts ants. (Elaiosomes are best seen locally in Bloodroot capsules following the flowering.) Having just read Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake and finding mycorrhiza are essential to my favorite hepatica patch in the woods, I wondered what was under the yellow trout lily. This abstract from New Phytologist shows the complexity of our knowledge of mycorrhiza:

|

“Costs and benefits of mycorrhizal infection in a spring ephemeral, Erythronium americanum” by Line Lapointe Julie Molard

New Phytologist 28 June 2008. "Spring ephemerals have evolved specific growth strategies that take advantage of the high photon fluence rates (the sun) of early spring. These strategies involve the sequential growth of different organs. Erythronium americanum (Ker‐Gawl), a common spring ephemeral of northern maple forests, produces its roots in the autumn, although stems and leaves develop in the spring. Mycorrhizal infection of the root system occurs very rapidly and intensively. The fungi thus depend on carbohydrate reserves accumulated in the corm (underground reserve organ) for their growth and development through the winter. We found that the presence of mycorrhizas drastically decreases root growth during the cold period and is more costly of carbohydrate reserves than root growth alone. However, during the spring, the presence of mycorrhizas fully benefits the plant: we measured an annual growth rate of mycorrhizal plants twice that of fungicide‐treated plants which were non‐mycorrhizal. We suspect that Yellow Trout Lily is highly susceptible to water stress during the growing season and might rely on its mycorrhizas for water supply to a greater extent than for nutrient supply. Nutrient uptake might occur mainly in the autumn when arbuscules are at their most abundant." |

I will stop here. My point has been made. One plant, the first we encountered, shows us the complex web-of-life where insects, fungi, other plants all are connected.

Lake Fairlee Nesting Loons

|

by Doug Tifft

6/6/21

6/6/21

|

As I write this we are a few days away from the hatching of what I hope will be the fifth successful brood of loon chicks on Lake Fairlee. The loon nesting raft anchored in the northeast corner of the lake has been occupied steadily since the evening of May 13. With a gestation period of 26 to 29 days, this is the week when one or two loon chicks will likely emerge. As the caretaker of the raft, which is visible from Route 244 and easily monitored from my dock, I am approached by lake residents at this time of year who want to know about “our loons.” I call them the rock stars of Lake Fairlee.

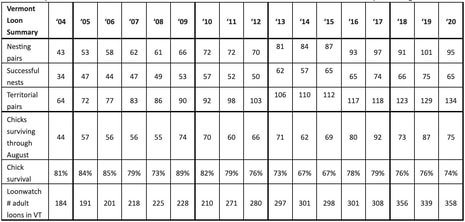

This loon pair has been returning to this same part of Lake Fairlee since first building a nest at the mouth of Blood Brook in 2016. Having successfully raising that first chick without assistance, they were eligible the next year for a loon nesting raft from the Vermont Loon Conservation Project after an initial nest failure on the island of Treasure Island due to predation of the eggs by a raccoon. The nesting raft was quickly installed on Memorial Day 2017 and, remarkably, the pair readily renested there and hatched another chick. Over the course of those first four years, this returning pair produced a total of five chicks, which is significant in a state that only had 75 loon chicks survive in 2020 (see chart). Last year our loons were prevented from using the nesting raft when it was preemptively occupied by geese. Undaunted, the loons established a nest on the shore not far from the mouth of Blood Brook again, only to have it fail due to predation by a suspected mink. Nesting rafts are an important factor in avoiding predation as well as flooding of the nest by changing lake levels and boat wakes. They clearly are also seen as deluxe accommodations by other birds besides loons. My role has expanded beyond maintaining and refoliating the raft each year to defending it until the loons get the urge to nest. |

|

I am regularly asked if I know for sure that this is the same pair of loons returning each year. While I can’t be positive without banding the birds, I have read that the male loon initially selects a territory and will return to the same spot each year and actively defend it, sometimes fighting challengers to the death. After six years, I also sense that this pair is at ease around me and fully expect their nesting raft to be waiting for them when the time comes. On May 2, I wrote to Eric Hanson, director of the Vermont Loon Conservation Project, with this observation:

The nesting raft as ice recedes in March

The nesting raft as ice recedes in March

My annual chores tending to the loon raft actually began more than a month earlier just as the ice was pulling away from the raft. It is left anchored in place throughout each winter. After being covered by snow and ice, it was a waterlogged, sorry sight, first requiring insertion of more flotation material that I shoved underneath in the chilly water. Then the soggy, dead vegetation and grasses from the previous year had to be removed.

Mindful of the geese incursion from the year before, I was determined to make a sturdier “goose guard” and have it in place by the time the marauding geese arrived. Last year, my more modest fence had blown off, allowing the troublesome geese access. This time, I constructed the barrier out of heavy 2 x 4s and attached wire fencing extending up 2 1/2 feet. I made it in two pieces for ease of installation and rowed it out through the skim ice on the first weekend in April.

Mindful of the geese incursion from the year before, I was determined to make a sturdier “goose guard” and have it in place by the time the marauding geese arrived. Last year, my more modest fence had blown off, allowing the troublesome geese access. This time, I constructed the barrier out of heavy 2 x 4s and attached wire fencing extending up 2 1/2 feet. I made it in two pieces for ease of installation and rowed it out through the skim ice on the first weekend in April.

I heard my first loon call on April 7 near the southern end of Lake Fairlee and then spotted loons at the northern end on April 10. Ducks had been back for some time and the sounds of geese could be heard in the marsh nearby. Geese nest more than a month earlier than loons and I thought I was adequately prepared. But I underestimated the urge to nest. Much to my surprise, I returned from a run on the evening of April 13 to discover that a goose had somehow landed inside the wire and appeared to be settling in. This portended a repeat of the disaster from the previous year. What to do?

Fortunately, when I came down to the waterfront early the next morning, I found that the goose and her partner were no longer on the raft, though swimming nearby. Seeing my chance, I returned with an armful of wooden stakes, rowed out to the raft, and closed off the top. The geese honked and looked on with disdain.

I assumed that I had acted in time, before they could lay eggs on the barren raft, which had yet to be refoliated. I saw no sign of a nest having been established and figured they were just trying it on for size. The previous year I had felt it was not my part to interfere with nature once I saw goose eggs in the nest. This year was different, I thought. A couple weeks later, I was pleased to see the geese had established another nest along the marshy shoreline on the other side of my waterfront. However, at the end of April as I prepared to refoliate the raft, I discovered I was mistaken and wrote to Eric Hanson with this observation:

|

“The only big surprise was that I discovered five goose eggs today as I worked to refresh the nest. I guess that goose I evicted a couple weeks ago was not just trying the nest on for size but really meant business. The eggs were rather deep in the nesting material which is why I did not notice them before. I assume they are no longer viable given the cold weather we have had since then. It is interesting that this same geese pair (at least I assume it is the same pair) successfully renested after their unfortunate encounter with me. They appear to hold no grudges.”

|

Eric advised me to remove the goose guard by May 5, which is near the time when loons get serious about looking for and claiming a nesting site. By May 2, though, I decided to begin replanting the raft and adding nesting materials. By then I confirmed that the geese had set up housekeeping elsewhere and I also observed heightened possessiveness of the raft by my loon pair. This included their intercepting and driving away beavers who had grown accustomed to visiting the cove where the raft was anchored in order to obtain sticks for a bank lodge on the shore of Treasure Island or to munch on vegetation emerging from the shallow water. I had never observed this sort of hostile interaction between loons and our plentiful beavers before. Aggresiveness normally occurs within a species as they defend territories from their own kind. Perhaps it was memory of the previous predations by raccoons and mink that provoked this behavior by the loons. It certainly made for exciting viewing as the loons approached the unsuspecting beavers like fighter jets, resulting in a tail slap and diving by the affronted beaver.

The loons were even hopping onto the nest for short periods that first week in May. Eric Hanson offered to stop by for an inspection and bring along some rooted shrubs to add to the nest. I wrote him the night before with this observation:

The loons were even hopping onto the nest for short periods that first week in May. Eric Hanson offered to stop by for an inspection and bring along some rooted shrubs to add to the nest. I wrote him the night before with this observation:

|

“Tomorrow at 8:30 a.m. sounds good. The loon, though, may be on the nest to help you with the shoveling. We saw a loon sitting on the raft at various times today as well as yesterday. The second loon was always nearby. Then they would be gone for a while. Maybe just house-hunting.

“By the way, we have five beavers who are quite active starting at dusk. They like to visit the little cove where the loon raft sits. Between the geese, loons, beavers, ducks, and osprey and eagles flying overhead, it is a bit dizzying. And there is a particularly large beaver whom I have dubbed the King Beaver that can be mistaken for a small bear when he comes out of the water. Who needs pets?” |

Eric’s visit early on the morning of May 5 was quite memorable. I thought I had better conduct some advance reconnaissance before he arrived. Standing on my dock like General Patton with my field glasses, I observed a brewing battle scene. Two geese were in the vicinity of the raft and were closing in, when suddenly the loons popped up between them and the raft. A small mallard (whom I dubbed the U.N. Observer Duck) was positioned nearby. Then from the other side of my dock, a convoy of eight geese landed, perhaps to back up their comrades or perhaps simply to watch the ensuing battle. The early morning air was tense with anticipation. I had to hurry away to prepare for Eric’s visit but wondered whether we would be visiting the raft for refoliation or to pick up bodies following a pitched battle.

I have learned that most animals will back down rather than engage in mortal combat after much posturing. A display of strength is often enough. When I returned to the waterfront with Eric half an hour later, we found no birds at all near the nesting raft. I described to him what I had seen developing and he clearly thought I had an over-active imagination. “Sounds like material for a children’s book,” he said. We loaded the rooted shrubs in my canoe and paddled out to the raft. I held the boat in position while he moved clumps of sod on the raft to create a windbreak and inserted the foliage. Just then, the two loons approached underwater and proceeded to entertain us with what appeared to be a ballet near the bow of the canoe. They swam back and forth, twisting and turning like dolphins, showing off or simply celebrating their recent victory. After more than two decades of observing loons, Eric said he had seldom experienced such a close encounter with loons in what appeared to be an expression of natural joy and animal delight.

The next weekend my daughter, Rosa, and I deployed the five loon nesting buoys to warn boaters away from the area. Lake Fairlee residents have become more and more protective of their loons and show great respect for this demarcation. While the occasional party boat or group of kayakers pause just outside the designated area once the loon is on the nest, there is almost a hush as they politely snap photos.

On the evening of May 12, I observed a loon standing on the raft busily rearranging the duff and dry grasses that Eric and I had placed in the nesting bowl. It was uncommonly fussy, moving one piece of grass at a time like a new homeowner unpacking and trying out different furniture arrangements. I had recently learned that loons are a close cousin to penguins. In fact, one of their behaviors when experiencing stress is called “the penguin dance.” As this loon awkwardly moved on its hind legs, which are so perfectly made for agile swimming but provide little mobility on land, I could see clearly the resemblance to penguins. The intense interest in nest building portended what must have been egg laying that night. From May 13 onward, the loon was almost constantly on the nest. I marked my calendar and began the countdown.

The nesting loon sits erect sometimes, panting with its mouth open, or may lay its head down close to the water, curious but undistracted as the occasional visitor files past at a respectful distance outside the buoys. It will take a brief break now and then to cool off in the water and presumably feed. Its mate is often nearby and they will visit, but soon the nesting loon clamors back onto the nest, standing awkwardly as it inspects and moves the eggs gently, before settling over them with a shimmy of its rear end.

When this pair established their first nest on the raft, I observed what we called “the changing of the guard.” The nesting loon would call out to its mate, who would dutifully return and takes its turn on the eggs. Then one year we were surprised to hear the calling out but did not see the other loon return. We jokingly referred to this negligent loon as “the deadbeat dad” and wondered if we should send the poor nesting bird some sustenance. My hunch now is that this was occurring when there were territorial threats from a group of intruder loons at the southern end of the lake. I was told by Eric Hanson that these bachelor loons were flying over from nearby Miller Pond. I began referring to the interlopers as “the Miller Pond gang.” Perhaps the “deadbeat dad” was busy fending off these unattached loons (though we sometimes wondered whether he was just off partying with them).

Now, as our loons have become more experienced parents, it appears that they work more in tandem, with the nesting loon taking more frequent breaks, though not swapping roles as they had during their early nesting years. I also observed what must have been a reunion of the extended family, when the nesting loon joined two others in a friendly, joint encounter. On the year when there were two chicks, a “nanny loon” showed up to tend to the first chick in the water while the nesting loon sat on the sibling egg that hatched a day later. The loon mate eventually showed up once the chicks were both hatched and became a dutiful parent again. During the first week after hatching, the two parents and the newborn chick leave the nest and establish what is called the nursery nearby, usually just off to the other side of our waterfront. One will dive for small fish to feed the chick while the other stays on the surface or allows the chick to hop on its back. The loon chick cannot dive underwater at first until it loses its fluffy feathers. After a few days, the loon family will venture further into the lake and we begin hearing reports from the extended Lake Fairlee Loon Fan Club about their latest parenting exploits.

My last duty each year is to take part in the annual loon count, which this year will take place between 6 a.m. and 10 a.m. on July 17. Every lake in Vermont will be surveyed by volunteers who report the number of resident loons spotted. It is a good excuse to circumnavigate our lovely lake early on a summer’s morning, scanning with binoculars for the whereabouts of any loons (while hoping not to be reported as a peeping Tom). If I am lucky, I will catch up with our particular loon family and extend my good wishes for yet another successful year.

I have learned that most animals will back down rather than engage in mortal combat after much posturing. A display of strength is often enough. When I returned to the waterfront with Eric half an hour later, we found no birds at all near the nesting raft. I described to him what I had seen developing and he clearly thought I had an over-active imagination. “Sounds like material for a children’s book,” he said. We loaded the rooted shrubs in my canoe and paddled out to the raft. I held the boat in position while he moved clumps of sod on the raft to create a windbreak and inserted the foliage. Just then, the two loons approached underwater and proceeded to entertain us with what appeared to be a ballet near the bow of the canoe. They swam back and forth, twisting and turning like dolphins, showing off or simply celebrating their recent victory. After more than two decades of observing loons, Eric said he had seldom experienced such a close encounter with loons in what appeared to be an expression of natural joy and animal delight.

The next weekend my daughter, Rosa, and I deployed the five loon nesting buoys to warn boaters away from the area. Lake Fairlee residents have become more and more protective of their loons and show great respect for this demarcation. While the occasional party boat or group of kayakers pause just outside the designated area once the loon is on the nest, there is almost a hush as they politely snap photos.

On the evening of May 12, I observed a loon standing on the raft busily rearranging the duff and dry grasses that Eric and I had placed in the nesting bowl. It was uncommonly fussy, moving one piece of grass at a time like a new homeowner unpacking and trying out different furniture arrangements. I had recently learned that loons are a close cousin to penguins. In fact, one of their behaviors when experiencing stress is called “the penguin dance.” As this loon awkwardly moved on its hind legs, which are so perfectly made for agile swimming but provide little mobility on land, I could see clearly the resemblance to penguins. The intense interest in nest building portended what must have been egg laying that night. From May 13 onward, the loon was almost constantly on the nest. I marked my calendar and began the countdown.

The nesting loon sits erect sometimes, panting with its mouth open, or may lay its head down close to the water, curious but undistracted as the occasional visitor files past at a respectful distance outside the buoys. It will take a brief break now and then to cool off in the water and presumably feed. Its mate is often nearby and they will visit, but soon the nesting loon clamors back onto the nest, standing awkwardly as it inspects and moves the eggs gently, before settling over them with a shimmy of its rear end.

When this pair established their first nest on the raft, I observed what we called “the changing of the guard.” The nesting loon would call out to its mate, who would dutifully return and takes its turn on the eggs. Then one year we were surprised to hear the calling out but did not see the other loon return. We jokingly referred to this negligent loon as “the deadbeat dad” and wondered if we should send the poor nesting bird some sustenance. My hunch now is that this was occurring when there were territorial threats from a group of intruder loons at the southern end of the lake. I was told by Eric Hanson that these bachelor loons were flying over from nearby Miller Pond. I began referring to the interlopers as “the Miller Pond gang.” Perhaps the “deadbeat dad” was busy fending off these unattached loons (though we sometimes wondered whether he was just off partying with them).

Now, as our loons have become more experienced parents, it appears that they work more in tandem, with the nesting loon taking more frequent breaks, though not swapping roles as they had during their early nesting years. I also observed what must have been a reunion of the extended family, when the nesting loon joined two others in a friendly, joint encounter. On the year when there were two chicks, a “nanny loon” showed up to tend to the first chick in the water while the nesting loon sat on the sibling egg that hatched a day later. The loon mate eventually showed up once the chicks were both hatched and became a dutiful parent again. During the first week after hatching, the two parents and the newborn chick leave the nest and establish what is called the nursery nearby, usually just off to the other side of our waterfront. One will dive for small fish to feed the chick while the other stays on the surface or allows the chick to hop on its back. The loon chick cannot dive underwater at first until it loses its fluffy feathers. After a few days, the loon family will venture further into the lake and we begin hearing reports from the extended Lake Fairlee Loon Fan Club about their latest parenting exploits.

My last duty each year is to take part in the annual loon count, which this year will take place between 6 a.m. and 10 a.m. on July 17. Every lake in Vermont will be surveyed by volunteers who report the number of resident loons spotted. It is a good excuse to circumnavigate our lovely lake early on a summer’s morning, scanning with binoculars for the whereabouts of any loons (while hoping not to be reported as a peeping Tom). If I am lucky, I will catch up with our particular loon family and extend my good wishes for yet another successful year.

Lake Fairlee Loons – March 2021 Update

by Doug Tifft

3/28/21

3/28/21

For the past decade, I have served as Lake Fairlee’s designated Loon Watch volunteer for the Vermont Loon Conservation Project, which operates under the auspices of the Vermont Center for Ecostudies. Residents of our lake community have grown increasingly fond of this distinctive bird with its haunting calls and vivid plumage. This has been especially true since 2016 when a nesting pair successfully hatched their first loon chick on a sandbar at the mouth of Blood Brook adjacent to where I live. The number of reports I receive from lakeshore owners has increased with each ensuing year as residents watch with delight the loon parents raising each year’s offspring.

This same nesting pair has returned each year since 2016 to the northern end of Lake Fairlee, where they have nested and raised a total of five chicks. Their steadfast efforts earned them a nesting raft the second year after their first attempt to nest on the island of Treasure Island failed due to predation by a raccoon. Thanks to the quick efforts of Eric Hanson, coordinator of the Vermont Loon Conservation Project (VLCP), the loons successfully re-nested less than a month later on the furnished raft anchored in the cove at the most northern end of Treasure Island. Given that fewer than 100 Vermont loon chicks survive each year, Lake Fairlee’s contribution to the total has been impressive.

In the fall of 2019, following our loons’ fourth successful year, Eric made this comment in a Valley News article titled “Loon’s Nesting Number Hits Record in VT”:

This same nesting pair has returned each year since 2016 to the northern end of Lake Fairlee, where they have nested and raised a total of five chicks. Their steadfast efforts earned them a nesting raft the second year after their first attempt to nest on the island of Treasure Island failed due to predation by a raccoon. Thanks to the quick efforts of Eric Hanson, coordinator of the Vermont Loon Conservation Project (VLCP), the loons successfully re-nested less than a month later on the furnished raft anchored in the cove at the most northern end of Treasure Island. Given that fewer than 100 Vermont loon chicks survive each year, Lake Fairlee’s contribution to the total has been impressive.

In the fall of 2019, following our loons’ fourth successful year, Eric made this comment in a Valley News article titled “Loon’s Nesting Number Hits Record in VT”:

|

[Eric Hanson] noted that the Upper Valley has one particularly good spot for loon canoodling.

“Lake Fairlee has been cranking out chicks for about four years now,” Hanson said, adding that one pair had produced chicks and there were other non-breeding loons spotted on the lake. “They’ve produced chicks every year that they’ve tried. That’s a little unusual. Usually there’s more failure.” |

In fact, the VLCP summary for 2020 shows that only three out of four nests on artificial nesting raft or on islands were successful. Loon nests on shorelines were only successful 14 percent of the time.

Our winning streak came to an end in 2020, though not through lack of trying by the loon parents. The loon couple returned this past year on April 8 to find their nicely appointed nest waiting their arrival. Preparing the nesting raft with small plants for shade and to serve as a windbreak, fresh “duff,” and dry grasses for a nesting bowl is one our first duties shortly after the ice recedes.

Our winning streak came to an end in 2020, though not through lack of trying by the loon parents. The loon couple returned this past year on April 8 to find their nicely appointed nest waiting their arrival. Preparing the nesting raft with small plants for shade and to serve as a windbreak, fresh “duff,” and dry grasses for a nesting bowl is one our first duties shortly after the ice recedes.

Loon nesting raft prepared with plants and a goose guard

Loon nesting raft prepared with plants and a goose guard

We also erect what is called a “goose guard” to discourage geese from occupying the nest first, since geese lay their eggs about a month earlier than loons. Unfortunately, high winds and choppy waters in mid-April dislodged one of the barriers. We discovered too late that a goose had occupied the nest and laid four eggs on the raft. Oddly, the loons did not seem terribly perturbed at first. We shared our ethical dilemma with Eric, who advised, “I let the geese do their thing. Hopefully the loons will wait it out, which they have in numerous cases before.”

Knowing when to stop playing Mother Nature is tough after preparing the nesting raft each year, deploying warning buoys, and once organizing a “loon rescue” by Eric when a loon became entangled in fishing line. The odds of successful hatches are made difficult by attacking eagles, territorial incursions by other loons, and shoreline predators. Who are we to forcibly evict geese who just couldn’t resist our accommodations? We watched and waited.

Ever stalwart, our loon nesting pair showed some annoyance with the geese, but eventually established a nest on May 17 in the marshes adjacent to the mouth of Blood Brook, very near to where they had initially set up shop in 2016. While we couldn’t

have been more pleased, it was with some surprise that four days later we found that the geese had abandoned the loon nesting raft, leaving four unhatched eggs. If only the loons had waited another week! We deployed warning buoys around the loons’ shoreline nest and made observations daily. Then, on June 3, we discovered the two loons swimming offshore away from the nest in what can only be described as a sulky mood. When they did not return to the nest the next day, I investigated and discovered that it was empty and broken shells were nearby. Most likely, a mink had driven the loons away and eaten the eggs.

Knowing when to stop playing Mother Nature is tough after preparing the nesting raft each year, deploying warning buoys, and once organizing a “loon rescue” by Eric when a loon became entangled in fishing line. The odds of successful hatches are made difficult by attacking eagles, territorial incursions by other loons, and shoreline predators. Who are we to forcibly evict geese who just couldn’t resist our accommodations? We watched and waited.

Ever stalwart, our loon nesting pair showed some annoyance with the geese, but eventually established a nest on May 17 in the marshes adjacent to the mouth of Blood Brook, very near to where they had initially set up shop in 2016. While we couldn’t

have been more pleased, it was with some surprise that four days later we found that the geese had abandoned the loon nesting raft, leaving four unhatched eggs. If only the loons had waited another week! We deployed warning buoys around the loons’ shoreline nest and made observations daily. Then, on June 3, we discovered the two loons swimming offshore away from the nest in what can only be described as a sulky mood. When they did not return to the nest the next day, I investigated and discovered that it was empty and broken shells were nearby. Most likely, a mink had driven the loons away and eaten the eggs.

We refoliated the nesting raft in hope that the loons would re-nest as they had done once before in 2017. However, our intrepid pair were not inclined to try again. In his 2020 report this past fall, Eric noted that other loons had established nests in late June and into early July. He also observed “a higher percentage of loon pairs taking the year off.” Who are we to know the minds and moods of loons?

Following the July 18, 2020, annual loon count, Eric reported that there were 358 adult loons counted on that day in Vermont. Previous loon counts were 339 in 2019, 356 in 2018, and 308 in 2017. So even though the count of surviving chicks for 2020 showed a dip to 75 from 87 the year before, the adult population appears to be stable. “The slight drop in productivity in 2020 can be explained by a higher percentage of territorial pairs not nesting and a lower nest success rate,” Eric wrote.

We eagerly await the return of our loons from the chilly waters of the Atlantic where they overwinter. Along with the more than 250 Loon Watch volunteers spread across Vermont, I will be ready to welcome them. We are fortunate that they have chosen Lake Fairlee as their home and that the shoreline community has shown them such hospitality.

Please feel free to send me your loon observations and any questions regarding loons at <[email protected]>

Following the July 18, 2020, annual loon count, Eric reported that there were 358 adult loons counted on that day in Vermont. Previous loon counts were 339 in 2019, 356 in 2018, and 308 in 2017. So even though the count of surviving chicks for 2020 showed a dip to 75 from 87 the year before, the adult population appears to be stable. “The slight drop in productivity in 2020 can be explained by a higher percentage of territorial pairs not nesting and a lower nest success rate,” Eric wrote.

We eagerly await the return of our loons from the chilly waters of the Atlantic where they overwinter. Along with the more than 250 Loon Watch volunteers spread across Vermont, I will be ready to welcome them. We are fortunate that they have chosen Lake Fairlee as their home and that the shoreline community has shown them such hospitality.

Please feel free to send me your loon observations and any questions regarding loons at <[email protected]>

A Email History of My 2020 Loon Mis-Adventures

April - June 2020

by Doug Tifft

Doug Tifft is Lake Fairlee’s designated Loon Watch volunteer for the Vermont Loon Conservation Project

Eric Hanson is coordinator of the Vermont Loon Conservation Project (VLCP)

Doug to Eric, April 20, 2020

I added some flotation under our loon nesting raft on Lake Fairlee and also put up a couple goose gates. Bonnie and I will be doing the tidy up and refoliating this week. We spotted the loon pair at a distance over the weekend, but loons have been sighted and heard around the lake for almost a couple weeks now (first loon sighting emailed to me on April 8).

Doug to Eric, April 21, 2020

Bonnie and I visited the loon raft yesterday evening in order to refoliate it. I found that one of my two goose guards had been either blown off or knocked off. To my surprise, I discovered four goose eggs in the nest bowl covered with duff. They appeared to be recent and intact. I had not see a goose sitting on the nest, though, since about a week and a half ago. I installed two goose guards shortly after that and it seemed to keep the geese away. All I can figure is that the very windy, choppy weather we had this past weekend may have knocked off one of the guards and a goose saw her opportunity and laid the eggs within the last couple days.

Bonnie and I completed our replanting around the nest bowl and along the portion of the raft facing the open water. We covered over the eggs and removed the remaining goose guard. Sure enough, there is goose sitting on the nest this morning with the male goose vigilantly floating nearby. And a loon was nearby just taking it all in but not seeming too perturbed.

We read up on the egg gestation period for geese and got the sense that, if the eggs are truly viable, there will be a goose occupying the nest through the middle of May. Does that sound about right? If so, will the loons still want to use the nesting raft and be willing to wait until it is vacated? We feel something of an ethical dilemma here, favoring one species over another. Shall we just let nature run its course? Or would you recommend we identify an alternative loon nesting area on the shore nearby and make it attractive by clearing away the surrounding brush and piling some nesting materials there? Or is it time to launch another loon nesting raft and this time nail the goose guards tight?

Eric to Doug, April 21, 2020

Not the first time. I let the geese do their thing. Hopefully the loons will wait it out, which they have in numerous cases before . . . Once geese move off, then I'd try to get out there to remove goose poop, add some fresh grasses and maybe a little sod/mud to tamp it all down for a fresh bed of sorts. Patience. and thanks.

Doug to Eric, April 27, 2020

The goose on the loon nesting raft is firmly established, with her mate standing guard as a sort of sentinel goose far off to one side.

I noticed, though, our loon pair often swimming nearby and without seeming particularly perturbed until recently. Yesterday evening, I observed the two loons approaching the nesting raft and positioning themselves about 10 feet on either side. Then one would dive with a big splash underneath the nest. They did this several times before casually swimming away. The goose (and the guard goose at a distance) did not respond at all.

Just wondering if this was a sort "shot across the bow" before the gloves come off. For the most part, the various species (ducks, geese, loons, herons) are very tolerant of one another. They mainly bristle when another of their own species gets too close to what is considering another one's territory.

Eric to Doug, April 27, 2020

I think you got it. Could they force the geese off? Stubborn and patient and don't react. Geese tend to win once on land. Swimming in the cove is another story.

Doug to Eric, May 18, 2020

Our eager loon pair could not wait for the geese to vacate the nesting raft. Yesterday evening Bonnie and I spotted a loon sitting on what we believe to be a nest about 20 feet northeast of the outlet from Blood Brook (off to the right as you face the shore) on the Matthews property. This is not far from the sandbar where this pair first had a successful nest four or five years ago. We plan to deploy the warning buoys this evening and will also send you a photo. Unlike that previous nest on the sandbar, this location is much better sheltered and not as visible to boaters (we almost missed it, in fact). It is also further into the shallows and not subject to boat wakes. The loons seem to know what they all about.

Otherwise, there is the usual bird activity with geese, a great blue heron who frequents this particular spot, scolding redwing blackbirds, regular fly-overs by a bald eagle, and an occasional visit by a cormorant directly out from our dock in the deeper water. An active family of beavers (at least three we have seen at a time) has established what I call Beavertopia a little ways up Blood Brook, creating a large backwater quite near our house that is teeming with life (and undoubtedly mosquitoes, though the bats have returned to help deal with that). We are well on our way to having our own mini nature preserve.

Eric to Doug, May 18, 2020

Good for them to find a spot. I'll be building better goose guards this summer out of solid 2x6 materials.

We'll see if raccoons or other predator finds the nest and eggs. Is nest vulnerable to kayaks? Do kayaks even get in very close there? If not, maybe no signs needed? Thanks for being on it.

Doug to Eric, May 23, 2020

It appears the geese were unsuccessful in hatching their eggs on the loon nest. We checked last night and found four unhatched geese eggs and the nest apparently abandoned. What should we do with the non-viable eggs when we clean off the nesting raft?

Otherwise, the on-shore loon nest and its watchful loon parent are doing fine. We kayak by once a day just beyond the buoys. It is a very well camouflaged nest and is well above the waterline.

Eric to Doug, May 23, 2020

Go ahead and clean off the raft. Eggs could go in the marsh behind it or bury.

Doug to Eric, June 4, 2020

I am sorry to report that the Lake Fairlee loon nest on the shore near the mouth of Blood Brook has been scavenged and the eggs are gone. I noticed the two loons quietly floating together just off shore from the nest yesterday morning but assumed they were just taking a break. When I went back yesterday evening at dusk, I was surprised to find no loon on the nest (see enclosed photo). I continued paddling further into the adjacent marsh and spotted a large mammal scurrying away from the shore of the inlet not far from the area where the loon nest was. At first I thought it might be a beaver because of its dark brown fur, but it moved more like a weasel and it headed away from the shore rather than into the water as a beaver would. I am guessing it was a large adult otter (or perhaps a fisher cat?) since it seemed to have no concern about getting its feet wet. Late last fall just after the ice appeared on Lake Fairlee, I observed three otters fishing off an ice floe near the shore. I am wondering if they roam along this marsh looking for turtle eggs and nesting waterfowl nests. I looked into the brush behind the loon nest to see if I could find evidence of the egg shells but only found the leathery remains of what appeared to be snapping turtle eggs. Only a mammal accustomed to dampness would have roamed out this far beyond the marsh.

Since our loons once re-nested after having their eggs taken by a raccoon on Treasure Island, I quickly cleaned off the remains of the geese nesting attempt on our nesting raft and added fresh duff to make it more appealing (see photo). I understand that we are not yet beyond the time when loons establish nests. Bonnie suggests I add a "vacancy" sign. Fingers crossed.

Eric to Doug, June 18, 2020

Hi all, wondering what the status is of the loon pair. I had hatch date for this week. Thanks.

Doug to Eric, June 18, 2020

I thought I had included you in the email reporting on the sad news that the eggs were scavenged, apparently by an otter I had spotted at about that time on the edge of the adjacent marsh. See below. I now see that I had sent the message twice to Eric Brooks when I meant to include you as well.

I was hoping that the loons might consider renesting using the vacated nesting raft but this has not happened. In fact, I seldom see the pair at all on this end of the lake, though we do hear loon calls regularly. I revisited the area where the loon nest had been and reexamined the eggshell remains. Upon turning them over I did see that they were speckled brown like a loon egg. Nature can be hard.

Eric to Doug, June 18, 2020

Thanks, Doug, for the update. Otter or mink. Raccoons can swim and love shorelines as sources of food. I usually think of otters as fish and crayfish eaters but I guess they can be opportunistic. We stil have some pairs nest searching both first time and re-nests so time will tell. I'll be making lots of new goose guards and can bring one down to you if you'd like. Thanks so much for all you've done.

Doug to Eric, June 25, 2020

I plan to circumnavigate Lake Fairlee around 6 a.m. on July 18 with my new binoculars (Father's Day gift!) at the ready. Thanks for your good guidance.

Our loon couple performed some wonderful synchronized swimming for us last night. Are they still likely to be engaged in mating behavior this late in the season? Before that, one of the loons was very playful as a beaver diligently crossed the lake towing a rather large tree toward a bank lodge under construction. This loon dove under the struggling beaver and then emerged behind and then in front of the beaver and then swam alongside. It almost seemed to be encouraging him in his hard work. (Remarkably, the beavers are building a bank lodge in addition to their existing lodge near their dam on Blood Brook. I didn't know that beavers were so adaptable.)

Eric to Doug, June 18, 2020

Thanks, Doug. Neat observations w/ the beaver. Yes, late for re-nest but not unheard of.

Eric Hanson is coordinator of the Vermont Loon Conservation Project (VLCP)

Doug to Eric, April 20, 2020

I added some flotation under our loon nesting raft on Lake Fairlee and also put up a couple goose gates. Bonnie and I will be doing the tidy up and refoliating this week. We spotted the loon pair at a distance over the weekend, but loons have been sighted and heard around the lake for almost a couple weeks now (first loon sighting emailed to me on April 8).

Doug to Eric, April 21, 2020

Bonnie and I visited the loon raft yesterday evening in order to refoliate it. I found that one of my two goose guards had been either blown off or knocked off. To my surprise, I discovered four goose eggs in the nest bowl covered with duff. They appeared to be recent and intact. I had not see a goose sitting on the nest, though, since about a week and a half ago. I installed two goose guards shortly after that and it seemed to keep the geese away. All I can figure is that the very windy, choppy weather we had this past weekend may have knocked off one of the guards and a goose saw her opportunity and laid the eggs within the last couple days.

Bonnie and I completed our replanting around the nest bowl and along the portion of the raft facing the open water. We covered over the eggs and removed the remaining goose guard. Sure enough, there is goose sitting on the nest this morning with the male goose vigilantly floating nearby. And a loon was nearby just taking it all in but not seeming too perturbed.

We read up on the egg gestation period for geese and got the sense that, if the eggs are truly viable, there will be a goose occupying the nest through the middle of May. Does that sound about right? If so, will the loons still want to use the nesting raft and be willing to wait until it is vacated? We feel something of an ethical dilemma here, favoring one species over another. Shall we just let nature run its course? Or would you recommend we identify an alternative loon nesting area on the shore nearby and make it attractive by clearing away the surrounding brush and piling some nesting materials there? Or is it time to launch another loon nesting raft and this time nail the goose guards tight?

Eric to Doug, April 21, 2020

Not the first time. I let the geese do their thing. Hopefully the loons will wait it out, which they have in numerous cases before . . . Once geese move off, then I'd try to get out there to remove goose poop, add some fresh grasses and maybe a little sod/mud to tamp it all down for a fresh bed of sorts. Patience. and thanks.

Doug to Eric, April 27, 2020

The goose on the loon nesting raft is firmly established, with her mate standing guard as a sort of sentinel goose far off to one side.

I noticed, though, our loon pair often swimming nearby and without seeming particularly perturbed until recently. Yesterday evening, I observed the two loons approaching the nesting raft and positioning themselves about 10 feet on either side. Then one would dive with a big splash underneath the nest. They did this several times before casually swimming away. The goose (and the guard goose at a distance) did not respond at all.

Just wondering if this was a sort "shot across the bow" before the gloves come off. For the most part, the various species (ducks, geese, loons, herons) are very tolerant of one another. They mainly bristle when another of their own species gets too close to what is considering another one's territory.

Eric to Doug, April 27, 2020

I think you got it. Could they force the geese off? Stubborn and patient and don't react. Geese tend to win once on land. Swimming in the cove is another story.

Doug to Eric, May 18, 2020

Our eager loon pair could not wait for the geese to vacate the nesting raft. Yesterday evening Bonnie and I spotted a loon sitting on what we believe to be a nest about 20 feet northeast of the outlet from Blood Brook (off to the right as you face the shore) on the Matthews property. This is not far from the sandbar where this pair first had a successful nest four or five years ago. We plan to deploy the warning buoys this evening and will also send you a photo. Unlike that previous nest on the sandbar, this location is much better sheltered and not as visible to boaters (we almost missed it, in fact). It is also further into the shallows and not subject to boat wakes. The loons seem to know what they all about.

Otherwise, there is the usual bird activity with geese, a great blue heron who frequents this particular spot, scolding redwing blackbirds, regular fly-overs by a bald eagle, and an occasional visit by a cormorant directly out from our dock in the deeper water. An active family of beavers (at least three we have seen at a time) has established what I call Beavertopia a little ways up Blood Brook, creating a large backwater quite near our house that is teeming with life (and undoubtedly mosquitoes, though the bats have returned to help deal with that). We are well on our way to having our own mini nature preserve.

Eric to Doug, May 18, 2020

Good for them to find a spot. I'll be building better goose guards this summer out of solid 2x6 materials.

We'll see if raccoons or other predator finds the nest and eggs. Is nest vulnerable to kayaks? Do kayaks even get in very close there? If not, maybe no signs needed? Thanks for being on it.

Doug to Eric, May 23, 2020

It appears the geese were unsuccessful in hatching their eggs on the loon nest. We checked last night and found four unhatched geese eggs and the nest apparently abandoned. What should we do with the non-viable eggs when we clean off the nesting raft?

Otherwise, the on-shore loon nest and its watchful loon parent are doing fine. We kayak by once a day just beyond the buoys. It is a very well camouflaged nest and is well above the waterline.

Eric to Doug, May 23, 2020

Go ahead and clean off the raft. Eggs could go in the marsh behind it or bury.

Doug to Eric, June 4, 2020

I am sorry to report that the Lake Fairlee loon nest on the shore near the mouth of Blood Brook has been scavenged and the eggs are gone. I noticed the two loons quietly floating together just off shore from the nest yesterday morning but assumed they were just taking a break. When I went back yesterday evening at dusk, I was surprised to find no loon on the nest (see enclosed photo). I continued paddling further into the adjacent marsh and spotted a large mammal scurrying away from the shore of the inlet not far from the area where the loon nest was. At first I thought it might be a beaver because of its dark brown fur, but it moved more like a weasel and it headed away from the shore rather than into the water as a beaver would. I am guessing it was a large adult otter (or perhaps a fisher cat?) since it seemed to have no concern about getting its feet wet. Late last fall just after the ice appeared on Lake Fairlee, I observed three otters fishing off an ice floe near the shore. I am wondering if they roam along this marsh looking for turtle eggs and nesting waterfowl nests. I looked into the brush behind the loon nest to see if I could find evidence of the egg shells but only found the leathery remains of what appeared to be snapping turtle eggs. Only a mammal accustomed to dampness would have roamed out this far beyond the marsh.

Since our loons once re-nested after having their eggs taken by a raccoon on Treasure Island, I quickly cleaned off the remains of the geese nesting attempt on our nesting raft and added fresh duff to make it more appealing (see photo). I understand that we are not yet beyond the time when loons establish nests. Bonnie suggests I add a "vacancy" sign. Fingers crossed.

Eric to Doug, June 18, 2020

Hi all, wondering what the status is of the loon pair. I had hatch date for this week. Thanks.

Doug to Eric, June 18, 2020

I thought I had included you in the email reporting on the sad news that the eggs were scavenged, apparently by an otter I had spotted at about that time on the edge of the adjacent marsh. See below. I now see that I had sent the message twice to Eric Brooks when I meant to include you as well.

I was hoping that the loons might consider renesting using the vacated nesting raft but this has not happened. In fact, I seldom see the pair at all on this end of the lake, though we do hear loon calls regularly. I revisited the area where the loon nest had been and reexamined the eggshell remains. Upon turning them over I did see that they were speckled brown like a loon egg. Nature can be hard.

Eric to Doug, June 18, 2020

Thanks, Doug, for the update. Otter or mink. Raccoons can swim and love shorelines as sources of food. I usually think of otters as fish and crayfish eaters but I guess they can be opportunistic. We stil have some pairs nest searching both first time and re-nests so time will tell. I'll be making lots of new goose guards and can bring one down to you if you'd like. Thanks so much for all you've done.

Doug to Eric, June 25, 2020

I plan to circumnavigate Lake Fairlee around 6 a.m. on July 18 with my new binoculars (Father's Day gift!) at the ready. Thanks for your good guidance.

Our loon couple performed some wonderful synchronized swimming for us last night. Are they still likely to be engaged in mating behavior this late in the season? Before that, one of the loons was very playful as a beaver diligently crossed the lake towing a rather large tree toward a bank lodge under construction. This loon dove under the struggling beaver and then emerged behind and then in front of the beaver and then swam alongside. It almost seemed to be encouraging him in his hard work. (Remarkably, the beavers are building a bank lodge in addition to their existing lodge near their dam on Blood Brook. I didn't know that beavers were so adaptable.)

Eric to Doug, June 18, 2020

Thanks, Doug. Neat observations w/ the beaver. Yes, late for re-nest but not unheard of.